Judith Warren: Health care equity then and now

When Health Care Access Now (HCAN) was started in 2009, the health care landscape in Cincinnati was even more divided than it is now.

Prior to HCAN’s formation, Judith Warren led the 20-county Regional Primary Care Access Initiative (RPCAI), an initiative sponsored by Interact for Health (formerly Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati). RPCAI united executives and leaders from the area and funded projects “that brought together the institutional side and community-based organizations to increase access to care.”

Though many were individually successful, Warren learned that “funding solo projects didn’t provide the growth and momentum we needed. An umbrella organization had to advocate for this work.” So HCAN was created as a data-driven project that bridged gaps in health care. She stepped in as HCAN’s first CEO, retiring in 2019.

Warren, who has a Master’s in Public Health and completed doctoral courses in Organizational Change & Leadership Development, had already established a career working with minority populations to achieve equity in health care. For example, she worked with the Michigan Cancer Institute in Detroit as part of a “targeted program funded by the National Cancer Institute to reach out to African American women who had previously not had pap smears or screening for cervical cancer.”

Serving as HCAN’s leader was a natural fit for her, and she contributed an enormous amount to its growth and philosophy, as well as to health care access for the community.

Stepping outside the walls

Warren says one big barrier to equity in health care in this region comes from “traditional health institutions and organizations not stepping outside their walls for outreach.” She stresses how access to specialty care and health education can contribute to prevention and reduction of chronic disease.

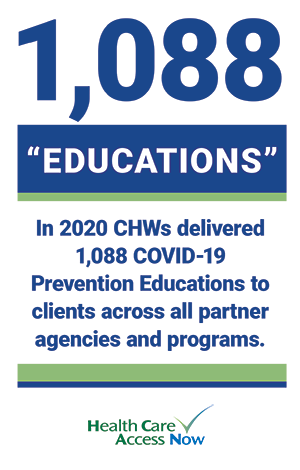

HCAN developed its Community Health Worker (CHW) program, using the Pathways Community HUB model (HUB), in response to this issue. CHWs—then and now—go out into the community to form relationships with clients. The HUB acts as a framework for CHWs to discover the root causes behind obstacles to good health outcomes and provide resources to eliminate them.

When HCAN started this program, it was “before implicit bias was even mentioned; it was a precursor to the discussion of equity, inclusion, and diversity. We had to have intentional focus and advocacy around cultural competency.” It was a much different approach than was being employed at the time. For example: “We were getting names from Ohio Medicaid Managed Care Plans to assist them in reaching and coordinating access to care and other resources. The plans had no idea where [their members] were because they were operating out of a centralized office, and telephonic case management was not working.”

Implicit bias correction in formative stages

Warren has seen some “definite improvements [to racial bias in health care] in tangible and practical ways,” citing a movement toward “having more people of color at the table, at the policy, steering, and planning committee level.” She says there seems to be greater focus on the sentiment behind the phrase “don’t do for people, do with people.”

But, she believes it’s still early days for the reckoning that needs to occur around implicit bias within the health care system. “You can’t correct a situation until you acknowledge that it is an issue,” she says.

It is now more readily admitted that social determinants—such as access to transportation, food, and housing—affect health, but implicit bias can be more difficult to accept because it is internal, personal, and often subtle.

“We’ve not completely connected the dots,” she says. To help correct the situation, she advocates for increased representation by people of color in all kinds of health care positions: “The health career field is so broad.” It is also necessary for health care institutions to promote “upward mobility inside of health systems—especially for African Americans, who can get pigeonholed into certain jobs.”

Still very much connected

Though Warren recently made a move to Atlanta, she’s “still very much connected to Cincinnati.” She continues to work with her church’s nonprofit organization, Zion Global Ministries (West Chester), which helps “low- to moderate-income families resolve financial gaps” through connection to resources.

That work keeps her tied to HCAN, too. “They refer clients who are eligible for financial assistance to us. We refer people—especially moms who are not aware of available benefits—to them.”

Warren’s influence on health equity in Cincinnati is undeniable. She created the foundation on which HCAN now stands.