Kimberley Stephens: Lowering the mortality rate, raising spirits

Kimberley Stephens likes to plant seeds in the community. “Sometimes you see the flower bloom, but sometimes you just know that the seeds have been planted and have the potential to grow,” she says.

Stephens is the Manager of Prenatal Outreach for Mercy Health. “We’re in the communities working with women during the prenatal stage to ensure that they’re doing the things they need to do for the baby and for themselves.”

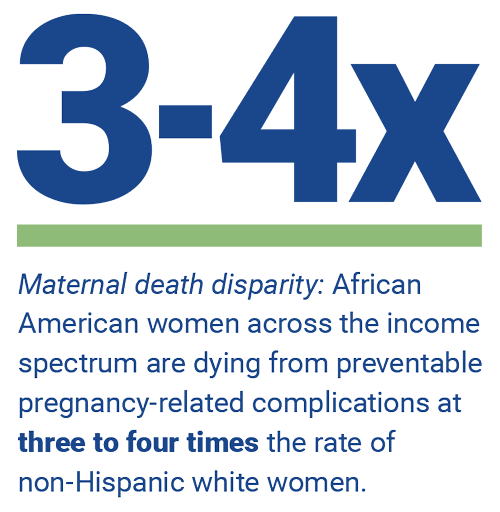

Her ultimate goal is to decrease the infant mortality rate among African American women. There are racial disparities in infant (and mother) mortality rates: “African American women…are dying from preventable pregnancy-related complications at three to four times the rate of non-Hispanic white women, while the death rate for [B]lack infants is twice that of infants born to non-Hispanic white mothers,” according to the Center for American Progress.

The role of CHWs

Stephens has two Community Health Workers (CHWs) working in the field under her supervision. “They’re heaven-sent. They have a heart for the work they do. They’re not there to judge, but to assist, educate, and make sure clients receive everything they need in order to have a healthy outcome for both baby and mom.”

The pandemic has required them all to change the way they interact with clients, but Stephens says that their flexibility has taught them new ways to reach people. “We’re doing virtual visits and are on the phone a lot. We do supply runs with little to no client contact,” she says. An unexpected advantage has been increased communication with clients. “They’re home more, so we’re able to reach them more easily.”

And, if the clients they serve are dealing with “grief, anxiety, depression, or are just overwhelmed,” Stephens is a licensed behaviorist who can work with them to make changes. Her CHWs do assessments to determine if this kind of intervention is needed.

Stephens says that the main takeaway from her position has been “to meet people where they are and not to assume people know things.” She has found that some of the women they service have not gotten sufficient information about pregnancy – “which makes it even more crucial that they attend doctors’ appointments.” She and her CHWs stress that “there are no silly questions” and encourage their clients to keep a binder so they remember to ask their doctors what they need to know.

Just getting started

Recently, Mercy Health partnered with HCAN in order to take advantage of the benefits of the Pathways Community Hub (Hub) model; HCAN is the Hub director for the Cincinnati region. As a Hub partner, Mercy can benefit from training, structure, and data. The Hub model breaks down typical barriers to good health outcomes by identifying obstacle categories, such as education, safety, and transportation. Then, partners can use this information to determine exactly what resources their clients need.

“We’re just getting started; we got our first set of clients not too long ago,” Stephens says. She tells the story of an outreach program she set up at an apartment complex. “A young lady walked up and wanted to know more. As we provided education and connected her with services, she teared up [with gratitude]. She was so willing and ready to work with us. It really solidified that we need to be out there connecting with pregnant women; they don’t know all the services there are to benefit them.”

That example is one of those instances where Stephens planted a seed and watched it start to grow. “I’m loving the work I do,” she says. “It’s my calling.”