Dr. Kamaria Tyehimba: Dismantling racial bias in addiction services

When the topic of addiction comes up, the opioid epidemic is currently top of mind for most people. How do you think about those who are addicted to prescription pain relievers, heroin, or fentanyl? Does race affect whether you label the addict as a victim or a villain?

It shouldn’t. Dr. Kamaria Tyehimba, who oversees the clinical side of the program as Director of Addiction Services at Talbert House, says that kind of bias is harmful and historical. It is within the fiber of our social system, and she fights against it every day.

“There’s a challenge to get people to accept that everyone has the same brain disorder if they are affected by a substance. One group isn’t criminals and the other victims,” she says. She has seen it in all kinds of situations: “committees, coalitions, written in policy, in board rooms.”

“People of color have been labeled as criminals,” who have seemingly “made a conscious decision to use drugs and become addicted,” but those labels haven’t been applied to everyone who gets addicted to opioids.

The truth is that “no one has ever chosen to be an addict, not a soul. No one thinks they will become addicted, that it can happen to them.” And then it does.

Talbert House’s role

“[Talbert House] provide[s] the whole array of addiction treatment, from outpatient to medication assistance treatment,” Tyehimba says. Her role is oversight of supervisors and direct care providers, acting in an administrative capacity.

She stresses that, “Talbert House is committed to equity and inclusion, and we’re working every day to get it right.”

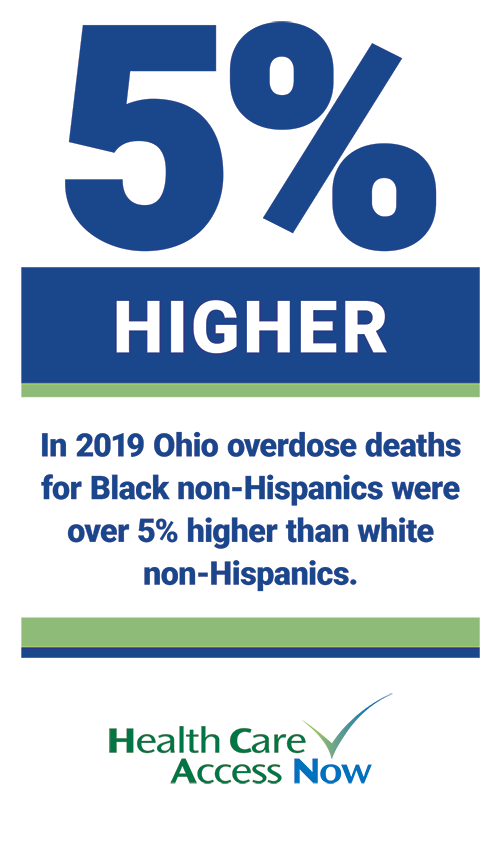

“Talbert House has far-reaching arms in my opinion,” she says. Here’s an example: Talbert House works with The Hamilton County Addiction Response Coalition. At first, the Coalition gave little focus to the overdose rate of African Americans. Tyehimba credits Talbert House for using its “influence, and social and health care capital” to help Coalition members see the importance of addressing opioid addiction and overdose in the Black community. The African American Engagement Workgroup was formed “to support closing the gap, allowing all the people who are suffering from addiction and overdose to be aware that treatment is available, affordable, and accessible.”

Talbert House works with Health Care Access Now to “ensure that our clients have access to care.”

“Look to your right, look to your left”

Tyehimba says biases are everywhere—and they’re often subconscious. “You can see it in the way plans and laws are written, zoning in a community.” These biases can be so buried that two people might be having a “conversation about how to treat people compassionately” and realize midway through that they’re “not looking at it the same way.”

To dismantle biases, she says it’s important to “be persistent” because “we only know what we know.” If her message doesn’t land one day, “I’ll come back to you in another day in another way. I have to hear what you say to figure out how to help you hear what I have to say.”

She believes people aren’t intentionally mistreating others, but they have to do the work to recognize where their own implicit biases lie. “Look to your right, look to your left. If everyone around you looks like you, you’re probably not addressing disparities, and it’s time to mix things up a little bit.”

Tyehimba has worked in non-for-profits in the mental health and substance use sectors throughout the entirety of her career. “No matter the venue, I have shown up and been available. I’ve given what I have to other people, whatever that is,” she says. And giving what she has makes an enormous difference in the community.