Why some HCAN clients resist medical homes

TRIGGER WARNING: References to health data and science experiments done on Black people.

A recent scene in the HBO series Insecure shows Molly rushing to the hospital to meet her family. Her mother has just had a stroke. The doctor approaches them and says it’s time to say their good-byes. The family is shocked. The white male doctor leads them to a hospital room where a Black woman lies in bed. But the woman is not Molly’s mother; she’s much older. The family tells the doctor this, and he says, “I know it can be hard to take. Strokes can really age people.” Molly says, “No, this is literally not her.” The doctor responds, “Are you sure this is not—” and Molly interrupts to say, “Yes, we are sure.” The family turns around to see another Black family coming into the room.

Of course, this is a fictional situation, but scenarios like this can be very real for Black people. This scene makes a point about the implicit bias of physicians. And, rather than admit his error, the doctor questions whether they, the family, are just having trouble recognizing their own mother/wife/sister. Yes, they are sure.

Long history of mistreatment

There’s a long history of mistreatment of Black people by the medical industry, whether that’s due to implicit bias or racial discrimination built into the system. Maybe you’ve heard of the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, which began in 1932. Three hundred ninety-nine Black men with syphilis took part in the study. They were not offered penicillin when it became the treatment used for the disease because researchers wanted to study the natural course of syphilis.

Maybe you’ve heard of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman, whose tissue samples were taken from her in the early 1950s, then widely used in research. Her cells “have been involved in key discoveries in many fields, including cancer, immunology, and infectious disease.” It’s wonderful that her cells have helped advance medical science, but her tissue sample was shared without her consent. Her family received no compensation. Her family wasn’t even told when scientists revealed her name and medical records, “and even published her cells’ genome online.”

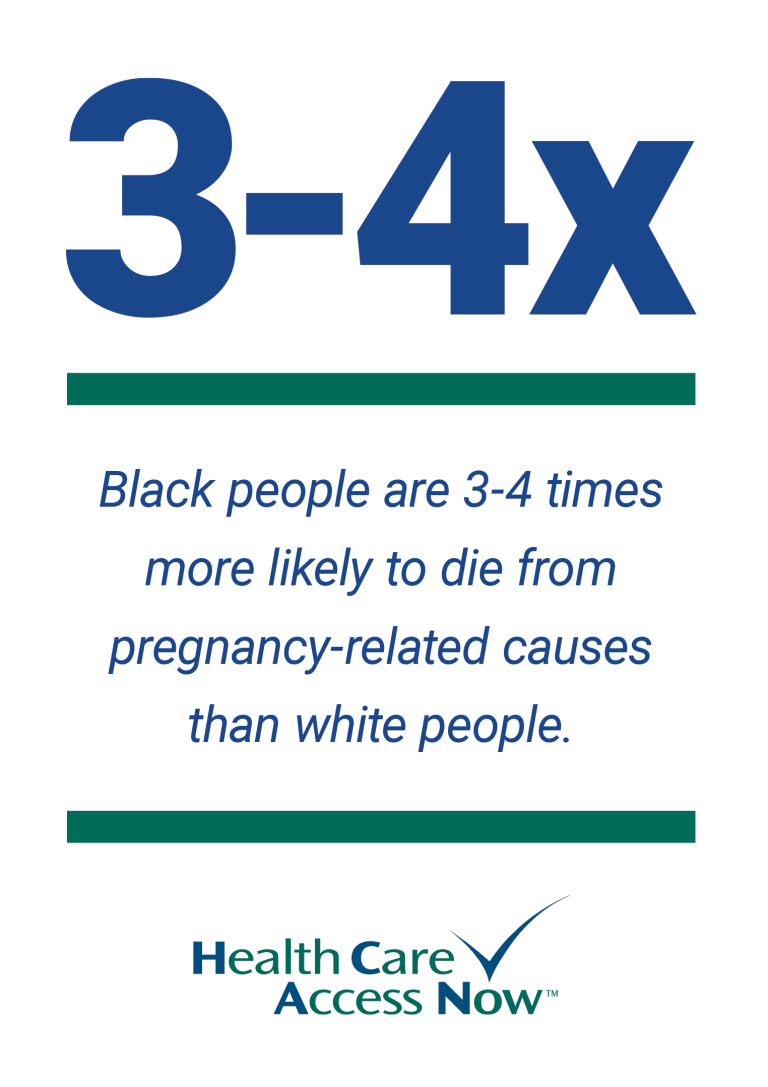

Or maybe you know that Black people have lower life expectancies than white people. Black men are more likely to suffer from hypertension than white men. There is a higher infant mortality rate for Black people (11 in 1,000) versus white people (5 in 1,000). Black people are less likely to be given pain medication than white people, due to incorrect beliefs about biological differences between race that still are held by white medical staff.

Mistrust of health care systems

Is it any wonder that many Black people don’t trust that their doctors have their best interests or good health in mind? It isn’t just the historical poor treatment of Black people in the name of medical science, it’s real experiences that they themselves have had or that they have seen happen to relatives or friends.

Health Care Access Now (HCAN)’s Community Health Workers (CHWs) address lack of trust when educating Black clients about the benefits of establishing a medical home, a place where their records are kept and where the doctors and medical staff know and support them.

They provide clients with important information and ensure they have a good experience when they establish care with a new doctor. People with medical homes can more easily manage chronic disease and benefit from preventive care.

Building trust with the medical staff, who can help clients learn more about managing their health, is an important step. Good health outcomes come from good medical care. But lack of trust for the medical system at large is a difficult obstacle to clear.