Health is not just determined by health care: Surviving isn’t enough

The study of the intersection of social sciences and physical health has revealed that good health outcomes are profoundly affected by life and demographic factors. According to the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, there are five domains into which social determinants of health can be categorized:

- “Economic stability

- Education quality and access

- Health care access and quality

- Neighborhood and built environment

- Social and community context”

Under each of those domains, more specific obstacles to health can be found. For example, food insecurity is a known barrier to health. That issue could have to do with both economic stability and with neighborhood and built environment (i.e. living in a food desert, or a place with inadequate easy access to healthful foods).

One of Health Care Access Now (HCAN)’s Community Health Workers (CHWs), Dwayne Wilkins Jr., says that some of these social determinants of health can be surprising to people who don’t encounter these issues regularly. They can even be surprising to the people they affect, simply because they’re so close to their own situation.

For example, how can “education quality and access” affect someone’s health? If an individual attends a school with less experienced teachers, large class sizes, and few resources, their learning opportunities are reduced. That can influence their ability to attain higher education, which can in turn limit their earning potential—and their health can be affected as a result.

Through in-home visits, CHWs certified by HCAN use the framework built by the Pathways Community Hub Institute (Hub) to discover what issues program participants face and work with them to overcome barriers and achieve independence. “It can be sensitive,” Wilkins says, “When you enter someone’s home, that’s very vulnerable.”

Survival mode

Wilkins says he has observed that mental and physical health are interconnected. “Depression can keep people from doing the things that are good for them,” he says. And, if someone is facing a lot of obstacles, it is unsurprising that they may begin to feel depressed.

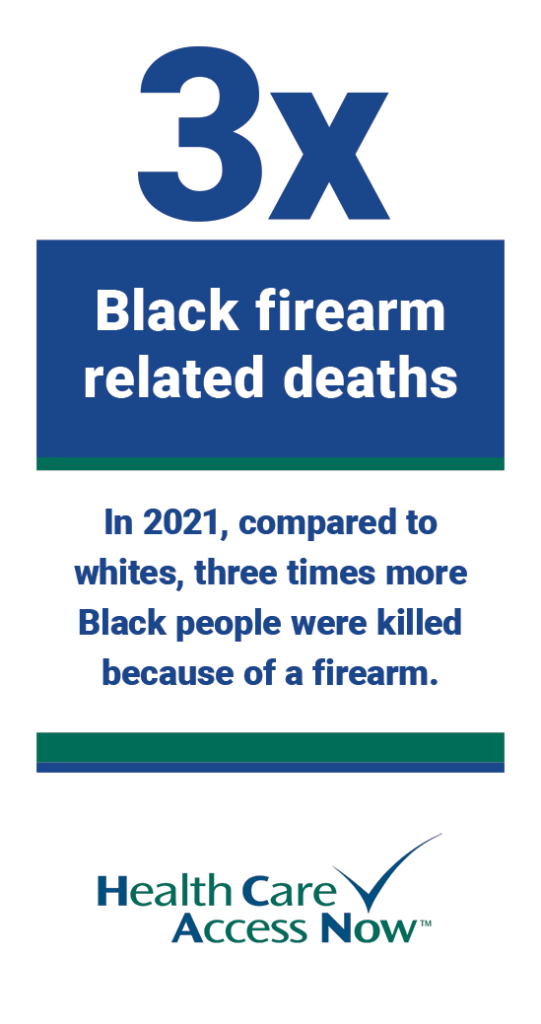

People facing a lot of hurdles can enter “survival mode,” according to Wilkins. That’s typical of someone who may be experiencing or witnessing violence, for example. When he suspects that a program participant may be experiencing domestic violence, he always relays that information to his supervisor, so HCAN can do background work on the individual’s behalf in case the participant does need or decide to use those resources. “It’s better to be ready than get ready,” he says.

Those situations may be complicated by all kinds of factors, such as finances, children, and whether there’s a weapon in the home. Once Wilkins establishes rapport, he asks questions designed to reveal the severity of the situation. “Do you know where the gun is, if it’s locked up? Do you need to remove yourself? When you’re in a situation like that, your main objective is keeping the perpetrator from becoming upset.”

Wilkins also has worked with participants who “carry [the effects of violence] for the rest of [their] life—and it’s both physical and mental.”

He says that health equity is achievable in the Greater Cincinnati area once policy is directed toward protecting and uplifting its people, “starting in the communities we’re neglecting.” Wilkins believes that more funds should be allocated to social services: “Individuals are facing drastic circumstances,” he says. Focus on the social determinants of health at a policy level can make a profound difference in the health and wellbeing of Cincinnati’s most vulnerable residents.