Low-income housing and landlord loopholes

The Housing Choice Voucher Program (formerly called Section 8) is a part of the Housing Act of 1937. The program was initiated in the early 1970s to assist low-income households with housing costs. People who receive vouchers—usually after a lengthy stay on a waiting list—have a limited period to find a place to live. It’s not an easy thing to do.

Why? Because not only is suitable affordable housing difficult to find, but also some landlords find ways around anti-discriminatory requirements.

Discrimination of protected classes prohibited

Fair housing laws in Ohio prohibit discrimination based on protected classes, including disability, familial status (usually meaning having children), and race. While most landlords do not overtly state that they will not rent to people who fall into a certain category, they sometimes make their preference known in more subtle ways.

For example, some landlords prefer for tenants not to have children because they believe they cause property damage. They may advertise an apartment as being part of a “quiet building.” This could signal to potential renters that families with children are not preferred tenants. Landlords may also simply not select tenants with children during the application process, stating that their reasons for rejection are unrelated to familial status. Neither of these practices is legal.

Landlords cannot ask tenants questions related to protected classes—like whether they have children—during the application process. A landlord may ask how many people will be residing in the unit, however, and make decisions based on that information.

[Community Health Workers’ housing Educations]

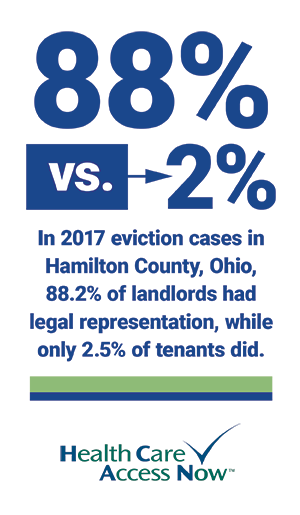

Eviction by harassment

Landlords who file for evictions overwhelmingly win their cases in Hamilton County (Ohio). One report studied a random selection of eviction filings from 2017 and found that “nearly half (49.9%)…were dismissed, 47.6% were decided in favor of the landlord, and only three cases, 0.4%, were decided in favor of the tenant.” This may be partially due to “disparity in legal representation.” In the cases reviewed for the report, “88.2% of landlords had legal representation, while only 2.5% of tenants” did.

Even though landlords who file for eviction through the court system are likely to win their cases, it is often a lengthy and expensive process. Some landlords attempt to force “problem” tenants to leave the premises by refusing to repair necessities or maintain the property, harassing the tenant, or raising the rent unexpectedly. These practices are illegal, as well.

Giacoma Telich, Community Health Worker (CHW) for Health Care Access Now (HCAN) talks about the profound effect that evictions can have on people. Evictions linger on public records for years, and many landlords will not rent to people who have been evicted. This severely decreases options and increases the likelihood of homelessness. Telich suggests that the system be changed so that an eviction is treated more like a misdemeanor. “Providing a second or third chance could make a big difference.”

Both tenants and landlords have legal obligations when they enter a lease. HCAN’s CHWs work with clients to understand their obligations and navigate a professional relationship with their landlords. Not every landlord is a good landlord, and not every tenant is a good tenant, but both parties need to know their rights and responsibilities.